By Dale Gieringer and Geoffrey Lawrence

Federal laws against marijuana are outdated and counterproductive. Polls show that nearly seven in ten Americans favor legalizing adult use of marijuana, and 90% favor medical use. Eighteen states have now legalized adult use of marijuana, and 36 have laws allowing medical use.

Nonetheless, federal law remains stuck in the past, strictly prohibiting marijuana as an illicit “Schedule 1” substance like heroin, treating it more stringently than cocaine or methamphetamines. As a result, it remains federally illegal for Americans to possess, grow, distribute, or transport marijuana, even for medical use and even where state law allows it. The conflict between state and federal laws has rightly led Supreme Court Justice Thomas to question the legitimacy of continued federal prohibition.

How then to reform marijuana laws? There is no one simple answer. A multitude of federal agencies and regulations are involved, and scores of different bills have been proposed to Congress. Recently, two comprehensive federal legalization bills have been introduced – the MORE Act in the House, and a new draft Senate bill by Sen. Schumer. Both get to the heart of the problem by removing marijuana from the list of controlled substances.

Descheduling is the keystone to marijuana reform because it lets marijuana be treated like other legal substances such as alcohol, tobacco and caffeine. While it removes federal penalties for marijuana use, it still allows states to regulate, prohibit, or legalize it as they please, like alcohol.

A weaker alternative, known as rescheduling, would regulate marijuana as a prescription-controlled substance like opiates. While this scheme is said to be favored by the Biden administration, it fails to accommodate existing state laws for both medical and adult-use marijuana.

Descheduling has the advantage of assuring that state-legal marijuana is equally legal under federal law. It also clears outdated federal restrictions on banking, medical access, research, immigration, housing, employment and gun rights.

Federal oversight of interstate commerce, including internet sales and promotion, foreign imports, and exports into states that prohibit marijuana would facilitate an orderly market.

But federal authorities needn’t comprehensively regulate and tax the entire marijuana industry, as presently envisioned in the Schumer bill. The latter would impose new federal rules on product testing, labeling, packaging, record keeping, cultivation, manufacture, inventory tracking, and FDA regulation of cannabis products. States already do all this and such regulation falls within their constitutionally reserved powers.

The federal role in cannabis regulation should rightly be restricted to products in interstate or foreign commerce. This might best be done through an agency like the Alcohol and Tobacco Trade Bureau, which has experience dealing with a diversity of state laws for similar adult-use products. In contrast, FDA regulation is notoriously costly and time-consuming, and the agency has a poor record of responding to consumer demand. The FDA is especially out-of-touch with medical marijuana, having repeatedly ruled that it lacks scientific proof of safety and efficacy, despite hundreds of studies to the contrary, and has stone-walled the legal hemp industry.

Some state tax regimes already make the black market more attractive to consumers and producers, and layering high federal taxes on top will exacerbate that trend. In California, where the total tax burden approaches 40%, more than half of the market is supplied by unlicensed dealers. A good case can be made that the total tax burden on cannabis should not exceed 15%, the amount currently placed on alcoholic spirits. Any federal excise tax should finance only the cost of facilitating inventory transfers between state regulatory frameworks, which should continue to govern product standards.

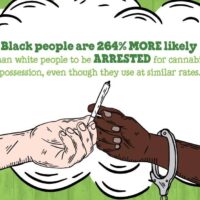

Finally, it’s essential that federal reform address the damage done by marijuana prohibition. Both House and Senate bills have restorative justice provisions to expunge or resentence persons for offenses that have been decriminalized. They also include equity provisions to ensure that prior offenders are not excluded from the legal market, and to promote competition and reduce barriers to entry for small entrepreneurs.

In the end, while there are many paths to cannabis reform, the wisest course is to free states from obsolescent federal laws, not further burden them with new federal taxes and regulations.

Dale Gieringer, Ph.D. is director of the California chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). Geoffrey Lawrence is director of drug policy at Reason Foundation and a founding member of the libertarian Cannabis Freedom Alliance.

An abbreviated version of this article ran in the LA Daily News.